By Greg Grishchenko, Industry analyst

Copy-cat labelling on private label products has created a lucrative revenue stream for discount stores, increasing confusion for consumers, and upped the champagne consumption of litigation lawyers. Industry analyst Greg Grishchenko reports.

Comparative advertising is also a subject of regulation by a number of federal, state, local laws and self-regulatory codes of conduct. Among them are the Federal Trade Commission Act and the section 43(a) of the Lanham Act, ratified in 1946 as the primary federal trademark statute of law in the United States.

The Lanham Act prohibits a number of activities, including trademark infringement, trademark dilution, and false advertising. However, 16 years into the 21st century, there is still no standard code of conduct for such advertisement in regards to policies and definitions. Confusion still goes on, creating frustration among leading brand owners – and obvious excitement for litigation lawyers.

In the highly competitive United States tissue market leading consumer product manufacturers like Georgia-Pacific (GP), Procter & Gamble and Kimberly-Clark are always targeted by other market players promoting their own products, especially private label suppliers who sometimes prefer not to reveal their manufacturing source.

In April 2015, GP filed a federal lawsuit against Aldi, the discount grocery chain with 1,400 stores in the United States, Solaris Paper, a US-based tissue paper converter, and an additional tissue product manufacturer. The complaint said the packaging of GP’s top brand Angel Soft toilet paper had been deliberately copied in details by Aldi for its Willow Soft Touch bath tissue. While court experts may have disputed any resemblance of baby pictures on labels or fonts of the word Soft, the offending phrase “Now with 15% more sheets than Angel Soft” was an issue involved in the eventual outcome.

It took four months for Aldi to agree for out-of-court settlement with GP. While specific terms of the settlement are unknown, judiciously-worded statements from defendant parties indicate that Aldi will change the packaging design of Willow Soft Touch to avoid resemblance with Angel Soft.

At the present time, six months after the GP-Aldi settlement, private label markings for tissue products have not changed much in its comparative ad wording. Aldi, the defendant in the lawsuit, did revise Willow Soft Touch labels. A red box with “15% more” words has gone along with a baby and a cloud, but the words “Compare with Angel Soft” remain intact as well as a disclaimer statement about the true Angel Soft brand owner.

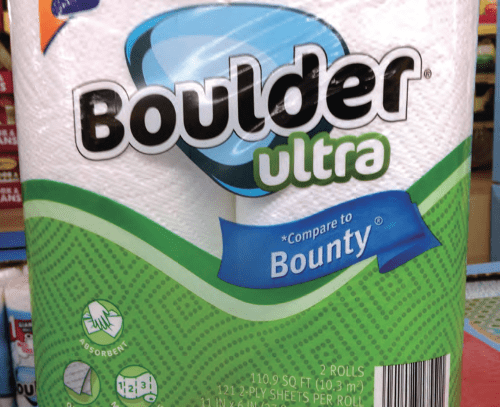

A notorious “Compare with” phrase even broadened to the other Aldi products including kitchen towels and napkins. Aldi’s private labels Willow and Boulder picked the other GP products such as Sparkle, Mardi Gra and Vanity Fair, Procter & Gamble’s Bounty and Charmin, and Kimberly-Clark’s Scott.

Aldi is not alone in tackling market icons. Many discount retail chains, drugstore chains, grocery supermarket chains and home improvement companies use “Compare with” wording on their private label tissue goods. Ad graphics may vary from quite visible coloured buttons to almost unnoticeable small font sentences combining the word “Compare” with a disclaimer.

Indeed a “Compare with” allegation seems to be a harmless thing asking a customer to go further in their shopping habits. The whole story is a gold mine for litigation lawyers and a nuisance for market leading brand manufacturers who spend hundreds of millions of dollars buying expensive tissue making machinery to guarantee their quality declarations.