Business-as-usual when utilising wood fibre is looking less likely for products such as tissue, as large policy readjustments for sustainability and forestry are currently taking place within the EU. AFRY Management Consulting’s Hampus Mörner, Manager, Carolina Berg-Rustas, Analyst, and Sami Pastila, Senior Principal, dissect for TWM the potential impact on wood fibre supply in Europe – and what the tissue sector can do more of.

Tissue paper is a product used in the daily life by billions of people around the globe for numerous hygienic and health purposes, and a paper grade that has more or less been in constant growth throughout the last few decades.

Volume wise, few if any other paper grades have shown such resilience towards economic turbulence, and where growing and ageing populations combined with improved living standards have proved to be key drivers.

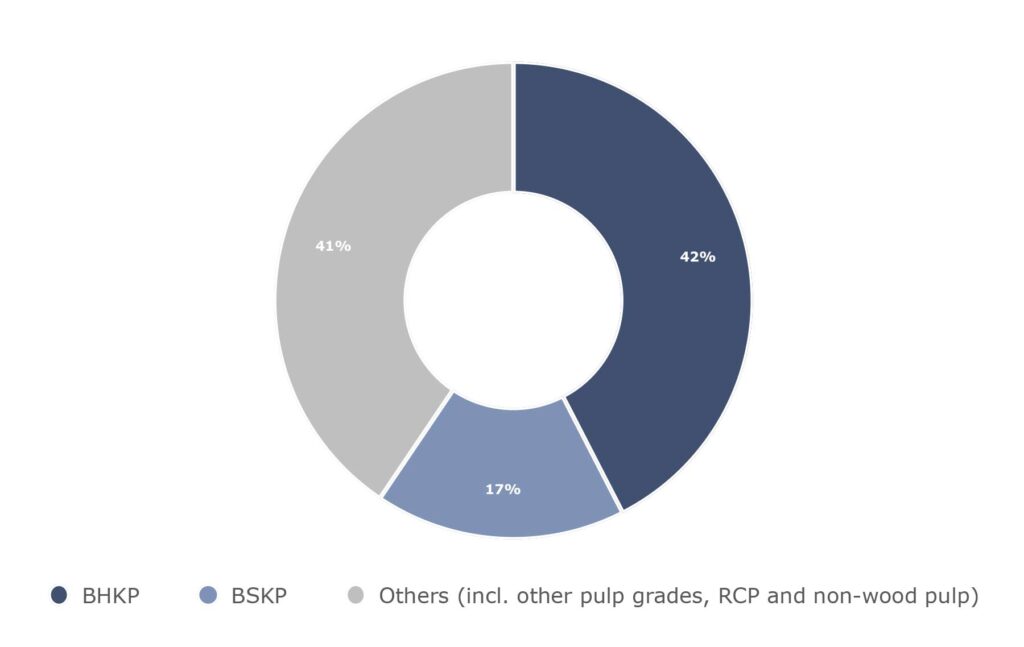

Most established tissue paper products are fibre-based, and wood fibre-based pulp dominates in the consumer tissue segment while recovered fibre is primarily used in the AfH segment.

Although there are several initiatives and investments in “new” or “less traditional” sources e.g. straw, bagasse or previously unutilised recovered paper sources, the tissue value chain looks to remain highly dependent on wood fibre for a long time to come.

Figure 1 indicates global furnish mix in tissue products globally. The trend is towards more hardwood (BHKP), although softwood (BSKP), providing robustness and strength to the products, will remain important. European fibre baskets play an important role in fulfilling the wood fibre demand for both pulp grades, although primarily for softwood where most of the fibre has its origin in the Nordics.

Wood fibre is a renewable and carbon neutral material which is a cornerstone in the work of phasing out fossil fuels and materials.

There are many great examples where wealthy and democratic economies go hand-in-hand with growing prosperous forests. Still, rarely has sustainability been such a hot topic for wood fibre value chains as today, where perhaps biodiversity and carbon storage are the most current issues. In a way, this is understandable as several motivated businesses are discovering the advantages that wood fibre brings when taking action for a green transition.

Despite many of the sustainable aspects with wood fibre, there are examples of “near misses” and actual “causalities” of being promoted as a part of the strategy to phase out fossils.

Although not necessarily justified, negative aspects with wood fibre are being intensely promoted. Business-as-usual when referring to utilising wood fibre looks to become a less likely event for a product like tissue, with a short life span and recycling challenges. Promoting the importance and advantages with wood fibre is becoming more important than ever.

One of the, so far biggest, policy readjustments for sustainability and forestry is currently taking place within the EU where the outcome can affect each step of the wood fibre value chain and the supply of raw materials. Below we examine a selection of recent policies and processes where central topics are biodiversity, carbon storage and potential impact on wood fibre supply in Europe.

Current key policies

Numerous policies and initiatives connected to the forest sector and its resources are under revision within the EU; the Biodiversity Strategy, Forest Strategy, LULUCF, REDII/III, the Taxonomy Regulation, Sustainable Carbon Cycles, Carbon Border Adjustment and the Deforestation Regulation among others. Each policy has its own timeline and the potential impact on the wood fibre supply chain can differ.

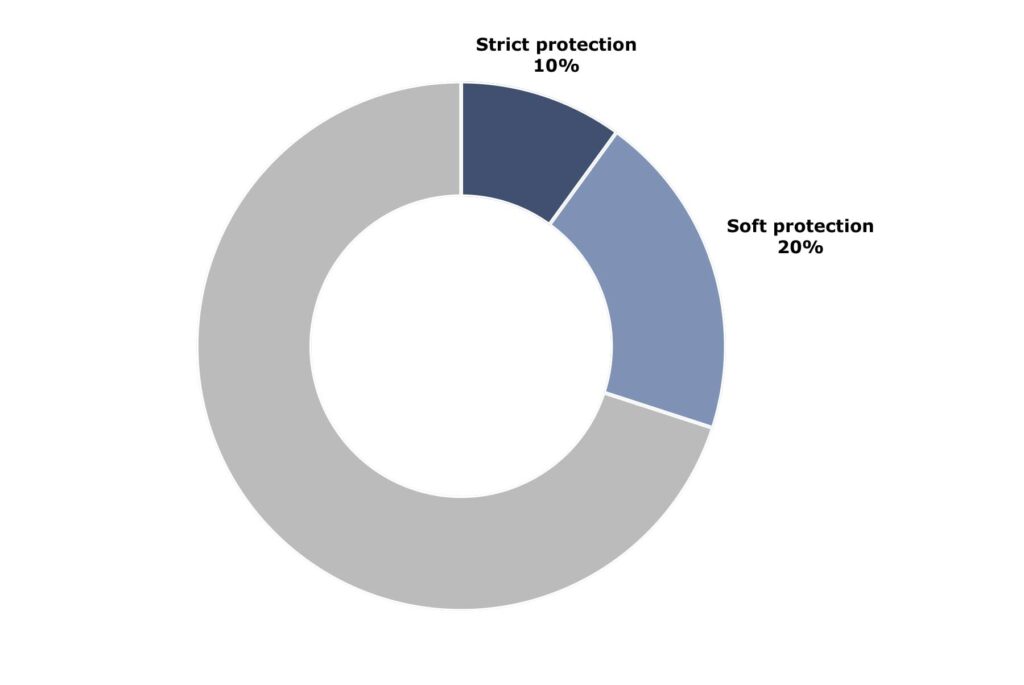

Biodiversity: Policies aimed at maintaining and strengthening biodiversity in the forest ecosystem are the Biodiversity and the Forest Strategy, the latter built upon the former. The main objective of the Biodiversity Strategy is to protect 30% of the land and 30% of the sea area within the EU. Of these 30% each, at least 10% should be strictly protected as illustrated in Figure 2. Legally binding nature restoration targets has also been introduced through this strategy.

According to the European Environmental Agency (EEA), 26% of the land area is currently protected within the EU. However, the share varies greatly among member states, largely due to variations in definitions of protection. Also, the share of strictly protected areas is not yet quantified. This implies that some countries would have to increase their protected areas, for instance the Nordic countries which according to the EEA currently protect almost 15% (Sweden and Finland).

Some EU countries like Germany might not fulfil the strict protection target, even though the overall protection target is fulfilled and therefore needs to increase the strict protection share. In either of the cases, this will likely restrict harvesting and harvesting potential if implemented.

As the Forest Strategy is built upon the Biodiversity Strategy, the main objective is to enhance biodiversity as well as contribute to greenhouse gas emission reduction targets. It promotes the use of wood fibre for long-lived products, rather than short-lived ones such as tissue, but also usage of continuous cover forestry and re-forestation. Wood fibre supply chains in many European countries are largely built on forestry without constant cover.

In addition to these policies, the new EU Deforestation Regulation, which is also aimed at safeguarding biodiversity, will increase the need for traceability of fibre through the value chain. In practice, the location of where the wood fibre was harvested needs to be reported for products entering or leaving the EU market.

Carbon storage: Policies aimed at carbon storage might also restrict the wood fibre supply in Europe through decreased harvesting levels. The main policies connected to this topic are the LULUCF and the Sustainable Carbon Cycles policy. The LULUCF Regulation is aimed at incentivising member states to decrease emissions and increase removals of greenhouse gases from managed lands (agriculture, forestry, etc).

A revision of the current LULUCF Regulation was agreed upon at the end of 2022, which will further enhance the role of forests in carbon removals. From 2026 onwards, carbon removal generated by forests and other managed land has to be larger than the emissions from these lands. Each member state will also have removal targets to be delivered by 2030. As forests are the main sink of the LULUCF-sector and the forest sink is initially reduced through tree harvesting, some member states have the pressure to decrease harvesting levels if there are no other ways to reach the removal targets set by the EU.

In addition, the Sustainable Carbon Cycles policy is aimed at promoting carbon removal activities in businesses primarily through the creation of a voluntary carbon market. In such a market, forest owners could theoretically sell carbon credits from standing forests, instead of wood fibre from harvested forests. Such a market would be a direct competitor to sourcing of wood fibre resources.

In all, the above stated policies can affect the wood fibre supply and production of tissue in Europe through:

• Increased forest protection (less land available for forestry)

• Changed forest management practices unsuitable for current practices (continuous cover forestry instead of final felling)

• Promotion of long-lived products instead of short-lived ones

• Increased need for supply chain traceability

• Decreased national harvesting levels (to maintain carbon removals on managed lands)

• Competing demand of the forest resource (from emerging carbon credit markets)

• Production leakage through shifted production from Europe to other parts of the world

• Accelerating trend for more hardwood in tissue furnish (primarily eucalyptus).

The road ahead

Even though there are numerous policies on the table, it is not certain if or to what extent the wood fibre availability will be affected as many of the processes are in the making. Still, there are clouds on the horizon for the industry where awareness, precautions, and measures become key. Potential actions and areas to address are elaborated below.

Sourcing: As known and stated above, the relatively short life span of tissue products vs the wood fibre brings challenges as new policy frameworks are produced. Although active and wealthy forestry can be an enabler for improved growth and carbon storage, it is hard to see that other “less traditional” fibre sources will not be an increasingly important part of the tissue furnish equation ahead.

Optimised sourcing and less waste are actual and ongoing steps, but so are initiatives and experimenting in new sources, both virgin fibre based and recycled. There are potentials and examples in collecting and recycling certain tissue grades as well as exploring new RCP sources e.g. cartonboards. Areas where the tissue sector potentially can do more with the right partnership and dedication.

Join forces: With the sizeable revision and work taking place the need for knowledge is of great importance. Industrial sectors dependent on virgin wood fibre have experience of cooperation on political and informative tasks, although to a large extent mainly within its respective sector, value chain and associations. The time to join forces, cross functional cooperation and focus on the common touch and pain points is more important than ever.

For instance, one of the greatest challenges in the sustainability framework is the development and refinement of indicators, metrics, and methodologies to measure progress towards targets set by companies. Knowledge is key in such a development work. However, knowledge not shared, informed, and communicated correctly to political decision makers in processes like the ones mentioned above is of little use, unfortunately.

Openness: There are learnings and areas of improvements in current forestry methods, and lessons are constantly learnt as biodiversity and carbon storage are taken more seriously than ever in Europe. As an example, forestry based on final felling and forestry based on continuous cover forestry are often opposed to each other as there is only one option.

Simplified, while final felling provides wood fibre from a limited land area, but with a visible footprint, continuous cover forestry demands more land to produce the same amount of wood fibre but with a less visibly footprint.

Each of the two systems, and practices between these two, can be suitable depending on local conditions and new solutions, technology and enablers (e.g. drones and improved data utilisation) are entering the market. Although traditional methods might as well be the correct way in many cases, openness, and a willingness to reconsider, fine tune, and challenge, is the key.

Promote: Biodiversity and carbon storage are complex topics and together they form the new frontier in future forest sustainability management. As with many frontier investments, experiments are needed to find new solutions. With uncertainty, new opportunities come. Businesses who are willing to act now rather than later will stand a great chance to shape the path.