By Industry analyst Greg Grishchenko

Even among developed ‘non-Western’ nations to ‘flush or not to flush’ is still the question.

Tissue – the brightest segment in the world paper business – is growing not only in volume but also in the minds of the global populace. Toilet paper is the dominant product and has for the last four decades been regarded as a key indicator of progress in society.

Public sewer systems in the majority of developed countries are designed to process used short-fibred toilet tissue without clogging. Modern septic tank services also assure bio-chemical dispersion.

“To flush or not to flush?” – this question divides people in Europe, the Americas, Asia and elsewhere. It is customary to find a trash bin next to a toilet bowl in the countries of the former Soviet Union and Balkans.

One example of the international news media’s reaction to toilet paper disposal came from the Sochi Olympics in Russia. American sport journalist Greg Wyshynski was affronted enough to post a photo of a restroom in Sochi with a sign that read “Please do not flush toilet paper down the toilet! Put it to the bin provided”.

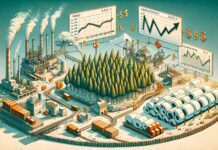

The ‘Western’ way of toilet tissue disposal is a topic of increasing public interest in ‘non-Western’ but relatively developed countries. But it is not simply an issue of efficient disposal … it sets recovered electrical power from incinerating toilet paper against minimal value from efficiently disposed sediment.

The sovereign and capitalist East Asian state of Taiwan is a regional economic power nearly 100 miles from mainland communist China. Like trading neighbour Japan, Taiwan too has a dwindling birth rate which continues to affect sales growth of tissue products, keeping it in low single digit numbers, while other segments of Taiwanese communal life enjoy impressive advance.

‘Taiwan’s manufacturers of quality toilet tissue brands claim that toilet paper consisting of short fibres will certainly break up in water and is therefore safe to flush.’

On a trip to Taiwan in November, I ascended to the top of Taipei’s 101 floor skyscraper in the world’s fastest elevator. One of the tallest buildings in the world, it boasts a 600 tonne, anti-wind vibration ball openly displayed at the top … a technological achievement which would make any city in the US jealous.

The Taiwanese tissue industry continued to show moderate growth in 2014, especially in the toilet tissue segment with Kimberly-Clark Taiwan and Cheng Loong Corporation leading the market.

Imports from China and Japan create competitive pressure in burgeoning consumer markets and drive up consumption from current five kg per year to European levels in some urban areas.

Taiwan stands out in the region of South East Asia, having first-rate public hygiene in most areas. Similar to Japan, this is a nation that makes its toilets and high rate of flush toilet usage important factors of the country’s “happiness index.”

The public obsession with the toilet can even be said to go to extremes; the “Modern Toilet Restaurant” is a well-known toilet-themed tourist attraction that has branches across the island. According to one of its owners the idea for the restaurant cropped up after reading the manga Dr. Slump on the toilet –Japanese comics string set around bathroom humour.

Perhaps surprising then that there should be any issue about disposability there of all places. The English-language daily, the China Post, recently laid out the continued debate about toilet paper disposal between Taiwan’s governmental Environment Protection Agency (EPA) and local legislators, siding with tissue manufacturers.

Taiwan’s manufacturers of quality toilet tissue brands Sujay (Kimberly-Clark Taiwan) and Andante (Cheng Loong Corporation) claim that toilet paper (but not facial tissue and kitchen towels) consisting of short fibres will certainly break up in water and is therefore safe to flush.

However, the EPA insists that the disintegration rate of toilet paper is low in the local sewer lines, causing blockages and multiplying costs associated with cleaning and repair. It also defends the advantage of getting recovered electrical power from incinerating toilet paper rather than minimal value from disposed sediment.

The “flushing toilet paper disposal” approach was first presented by Taipei politicians in 2007 during a high-profile conference.

The capital city’s Environmental Protection Department, however, was reluctant to promote toilet tissue flushing, claiming that some members of the public would throw non-tissue items like newspapers and sanitary pads into toilets and cause sewer line blockage.

On the contrary, defenders of flushing suggest the government agency should also consider saving energy while collecting toilet paper waste and hold back purchase of otherwise avoidable toilet paper bins and waste bags.

The debate is on-going, even as Taiwan’s positive economic prospects will likely increase tissue use and lend weight to both sides of the argument.