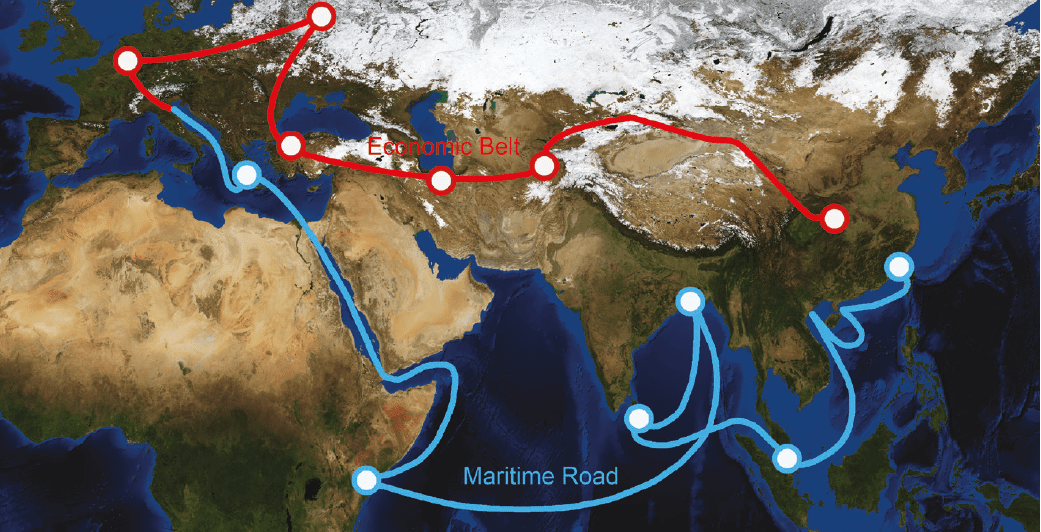

China is a major financier to the world. Just one of many investment vehicles is its initiative to transform transport systems and smooth trade across Asia, Europe and Africa – estimated at $900bn of projects planned or underway to date. Four years on from launch, initial doubters are being won over, while obstacles remain both abroad and at home. A TWM report.

It was the magnitude of the project – probably the most ambitious in scale and scope in the world today – which had many in the West shaking their heads at China’s One Belt, One Road policy, known as OBOR, at its launch in 2013.

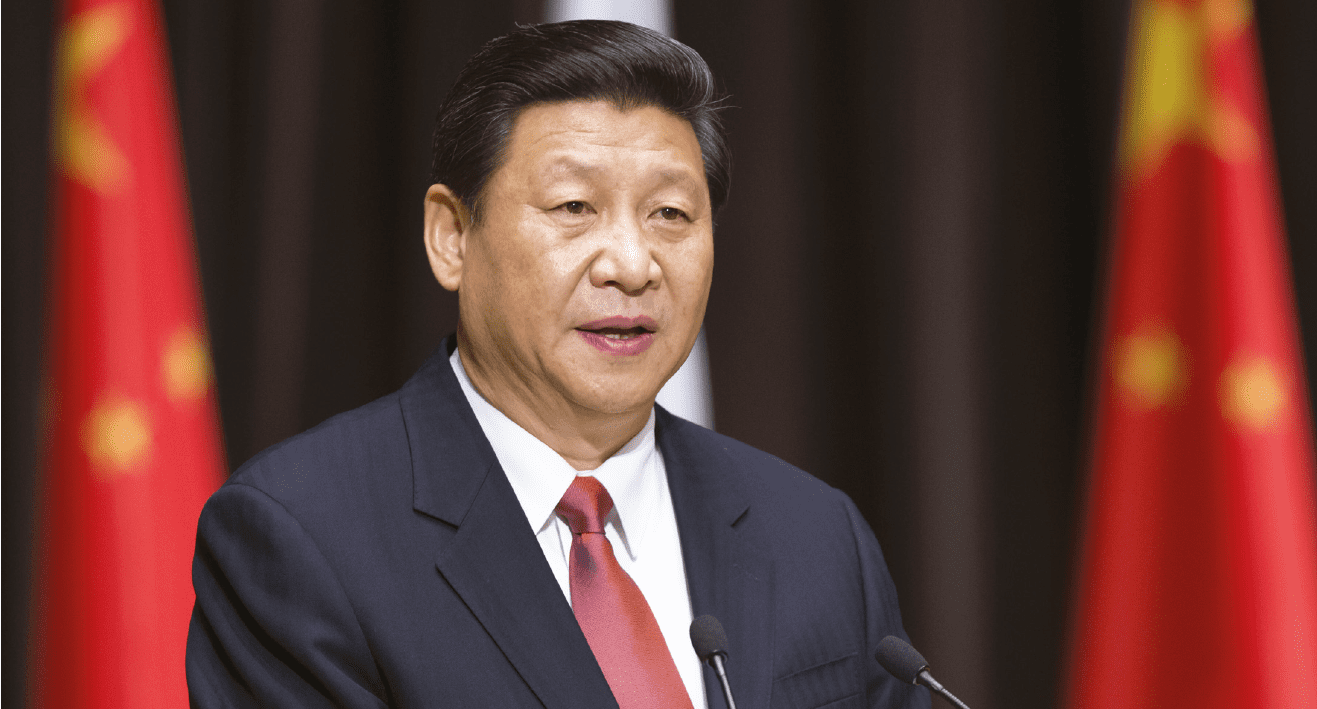

Xi Jinping was nothing if not epoch defining in his vision. OBOR would, said the President, add “splendour to human civilisation” and help build a new era of harmony and trade across the globe.

The historic “project of the century” would transform swathes of the developing world and grease the wheels of trade as never before along a veritable network of Silk Roads.

A massive economic zone connecting Asia, Europe and Africa through a network of highways, ports, bridges, tunnels and pipelines, and deep water ports in the Arctic, could involve 70 nations and directly or indirectly affect two-thirds of the world’s population.

More recently he has said: “Economic growth is not on solid ground … globalisation is encountering headwinds. Development has become more uneven – not to mention the other challenges that overshadow the world economy such as wars, conflicts, terrorism and a massive flow of refugees and migrants.”

It followed, therefore, that world leaders should reject protectionism, embrace globalisation and pull together. Cooperation was the only way to confront the “profound” changes sweeping the globe.

It happened that Mr Xi was speaking in front of some of those world leaders – Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Pakistan’s then Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and Myanmar’s Aung San Suu Kyi – but not Donald Trump, Angela Merkel, Emmanuel Macron or Theresa May – at an economic summit in Beijing’s Mao-era Great Hall of the People. He reached for a poetic metaphor: “Swan geese are able to fly far and safely through winds and storms because they move in flocks and help each other as a team. The message is: the best way to meet challenges and achieve better development is through cooperation.”

Suspicions quickly surfaced in western, and some Asian, capitals: this was nothing more than a means to swamp markets with Chinese goods; a ruse to boost China’s own economy by shifting vast excess industrial capacity in cement, steel and other metals to less developed nations and drawing poorer countries tighter into Beijing’s grip; and a protracted search for more profitable homes for China’s vast foreign-exchange reserves, most of which are in low interest-bearing American government securities.

Nations threatened not to sign up unless free tendering was guaranteed for OBOR contracts; France, Estonia, Greece and Portugal were reported to be withholding support; India went public with its opposition to what one newspaper called “little more than a colonial enterprise.”

To some extent the landscape is changing now, not least because new roads and railway lines are actually being laid down and are beginning to transform it. Tendering has been open. Western multinationals are piling in and making multi-billion deals to sell equipment, technology and services to Chinese firms doing the building.

Hundreds of projects are up and running, many linked to China’s extensive pre-OBOR investment projects for water and waste, energy, telecoms, social and health provisions, banking and legal services.

Given the broad geographical scope and objectives of OBOR, and the secretive nature of some of the countries in which it operates, a comprehensive accounting is difficult, and is further complicated by the vast number of private, public and international institutions involved.

But some idea of that scope is possible as new projects get underway and others which have been under construction for many years are linked in. Specific OBOR projects include much construction underway in China itself, still a developing country. By 2020 the highway expressway network will increase from 74,000 to 139,000km, rail lines from 91,000 to 120,000km, the number of airports from 175 to 240.

OBOR comes at a time when Asean (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) is hungry for infrastructure financing. The Asian Development Bank estimates that the region needs US$5.5 trillion from 2015 to 2030. China’s outward direct investments (ODI) into Asean surged by 87% by 2015.

Major recipients are Vietnam, Indonesia, Cambodia, Malaysia and Loas where, for example, work on a 400km railway link to China began at the end of 2015. OBOR money has helped to put Singapore in a position to earmark 12.5% of annual income towards further improving its already superb transport systems. Hong Kong and Macau will soon have a massive bridge link, due to open later this year. Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan, is investing in a high-tech rail system, built by the Chinese. A high-speed railway is due to be operational in Thailand by 2021.

A $46bn China-Pakistan economic corridor is underway where China has since the 2000s been financing the construction of a major port, as it has in Myanmar, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

In Africa, China is already the single largest investor across a wide range of projects. China-Africa trade rose from US$10 billion in 2000 to US$220 billion in 2014, with Chinese companies purchasing stakes in mining operations in return for loans to finance large-scale infrastructure projects. A high speed railway between Mombasa and Nairobi opened this year, and there are plans to extend it further into Africa’s hinterland. Big borrowers are Angola, Ethiopia, Sudan, Kenya, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

And as an example of OBOR’s reach into the far western edge of Europe, Mr Xi himself visited Manchester Airport in the north west of the UK to launch the first direct flight to Beijing as part of a £800m business park project involving Beijing Construction Engineering Group to improve air and shipping links. The first freight train connecting China directly to the UK travelled 7,500 miles on its maiden journey – making it the second-longest route in the world.

OBOR funding links are in the pipeline with other major UK companies including BP, London Metal Exchange, Arup, Standard Chartered, KPMG and HSBC to provide a range of specialist services across the OBOR zone.

That zone of operations could, too, expand. Beijing has said the initiative is “an open and inclusive one,” and welcomes participation in countries where Chinese banks and companies are already financing a wide mix of development contracts.

They streamed $118bn to Latin America between 2007 and 2014: 53% to Venezuela, 19% to Brazil, 12% each to Ecuador and Argentina. China is currently the largest trade partner of Brazil, Chile and Peru. Latin America mostly exports primary goods and natural resources to China, such as copper, iron, oil and soybeans. In 2015, President Xi pledged to double bilateral trade links to $500 billion and increase investment to $250 billion over the next decade.

President of Chile Michelle Bachelet, already committed to promoting a Trans-Pacific optic fibre cable to improve digital connectivity between Asia and Latin America, is looking, with other nations, to the possibility of OBOR funding for tunnels and highways across the Andes Mountains and ports to link Latin America and South America to Asia.

Chile’s ambassador to China Jorge Heine said in a recent column in China’s Global Times that South America should make the most of the opportunity: “For South American countries, poised to make the big leap toward being fully developed nations, but not quite there yet, their association with Asia represents the best hope to make that happen.”

As with Chile, potentially so with many other nations poised to make that big leap.

Sources: Fitch, Thomson/Reuters, BMI Research, Global Economy and Development, HSBC.

New roads and new belts could reach tissue’s greatest untapped markets… given time

Tissue is a good litmus test of living standards… the more income, the more and better tissue products bought. That has long been a guiding principle. For shoppers, and societies, to reach that happy position they need ‘hard’ stuff: roads for articulated lorries to thunder along on the way to superstores; bridges to cross the rivers; tunnels to link communities living at different ends of mountains and countries; fast railroads; deep water ports; shipping highways. The AfH market needs a smooth ride to get to that 5 Star hotel.

In the general sense, any improvement in logistic capability will improve all trade. Sustainable infrastructure underpins all economic activity. Inadequate infrastructure remains one of the most pervasive impediments to growth and sustainable development, and consequently in tackling lower incomes.

Good infrastructure unshackles and removes constraints on economic growth and helps increase output and productivity. Investment in sustainable infrastructure can help generate employment, boost international trade, industrial growth, and competitiveness, while reducing inequalities within and among countries.

The hard fact is that infrastructure is ageing and massively under-funded across the globe, including across the US. Transport systems which helped power the success of leading manufacturing nations from the 19th Century onwards are crumbling.

Many of those nations have simply not begun to parallel multi-infrastructure improvements with the growth of entrepreneurial advances they are making in other fields. A transport backlog is the result, costing billions in delays, damage and half-measure, piecemeal repairs. Developing countries have yet to catch up. Some are making rapid strides, others are barely walking at all.

One Belt, One Road proposes an activist view of development scaled up to the level of three, and probably more, continents.

It has been said that OBOR exceeds the Marshall Plan through which the US loaned over $132bn at current dollar value to help rebuild European economies after World War II. It has a particular relevance for tissue because in large part the regions where infrastructure is poor are the regions of greatest untapped potential growth for tissue products.

TWM’s recent Country Report from India was one glaring example among many. The economy is the sixth-largest in the world measured by nominal GDP and the third-largest by purchasing power parity.

The country is classified as newly industrialised, and one of the G-20 major economies, with an average growth rate of approximately 7% over the last two decades.

Yet huge swathes of the country suffer from poor infrastructure where the rapid and cost-effective delivery of manufacturing and retail services simply haven’t been able to reach. This is tissue’s biggest untapped market.

TWM’s Brazilian coverage highlighted the huge potential of the vast north eastern region currently ill-served by transport links. The same could be said of other regions of the continent where once outside of the cities transport systems serving considerable populations ranges from difficult to a hardship.

Equally sub-standard transport systems are a hindrance to trade in other key tissue regions … in the rural, provincial regions of Vietnam, Thailand, Russia.

There are cultural, political and security reasons holding back tissue’s advance in many regions, but successive younger generations with more modern outlooks and better means of transport are beginning to influence market trends more. Given the base funding the road ahead for tissue could reach further and further.

Many obstacles along the way

The ‘challenges’ acknowledged in Xi’s vision are many, both externally and internally.

Most of its land routes pass through countries, and not least China’s own unstable western regions, that are already politically unstable or are at risk of considerable upheaval over the coming decades. Beyond its trade objectives, OBOR has been seen as a bid to enhance China’s international connections and expand its geopolitical influence much further westwards, and thereby play a greater role in shaping Eurasia’s security relationships as well as its trading patterns.

A potential minefield if ever there was one. A potential backlash loomed in Europe when officials spoke of Chinese companies evading capital controls, smuggling money out of the country by disguising it as OBOR funds.

Investment in some of the world’s more blighted regions is inherently fraught. Over-reach by the risk-hungry China Development Bank and China Eximbank could stumble, and there is reported to be infighting between the most important Chinese institutions involved, including the ministry of commerce, the foreign ministry, the planning

commission and China’s provinces.

To make matters worse, China is finding it hard to identify profitable projects in many belt-and-road countries (Chinese businessmen in central Asia call it “One Road, One Trap”). Further, China is facing a backlash against some of its plans, with elected governments in certain countries repudiating or seeking to renegotiate projects approved by their authoritarian predecessors.

A recent OBOR forum showed signs of a backlash against the project that may have confirmed some Europeans in their decision to stay away. Yet the suspicion that the project will fail could be misguided. Mr Xi needs the initiative because he has invested so much in it. China needs it because it provides an answer of sorts to some of its economic problems. And Asia needs it because of an unquenchable thirst for infrastructure. Problems or not, Mr Xi is determined to push ahead.

‘There is another side to this process’

Euromonitor’s head of tissue and hygiene industry Svetlana Uduslivaia points to clear benefits for China’s tissue industry through improved logistics and exports provided other markets don’t impose restrictions on cheaper Chinese goods if the flow increases.

She said: “China’s tissue industry has been struggling with domestic oversupply, and access to foreign markets is important. The unmet potential in a lot of Asian markets as well as Africa is very substantial, and there are significant opportunities there. “India’s unmet potential in consumer retail tissue is estimated to be in excess of US$10 billion; well over a US$1 billion in Russia, Egypt at over US$1 billion, Nigeria at close to US$2 billion.

“Many markets have already seen an influx of cheaper Chinese tissue, which added to competition and put pressure on other brands (both international and domestic). Improved logistics for China’s industry would mean better / easier and more cost efficient access to foreign markets.

“Good news for Chinese tissue manufacturers and suppliers. Also good news for consumers in the developing markets where there is a need for more affordable products.

“But not likely to be met with enthusiasm by many international and domestic manufacturers of tissue because of still more competition and more pricing pressures at the times of already tight margins.

“So, there is another side to this process: China might be seeking improved access to foreign markets, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that every country will just open up more. US is just one example, as it imposed anti-dumping duties on Chinese tissue imports.”

Analyst Greg Grishchenko said: “With the limited growth in local consumption China is in constant motion to use vast tissue forming capacity acquired during the latest decade. While the process of eliminating small non-effective tissue producers inside the country is almost completed, the network of new shipping routes, railroads and bridges as part of

Belt and Road plan might bring similar deeds to countries of not only Asia but America, Australia and Africa as well.

“Building new infrastructure capacity across Asia and beyond might deliver significant increase in jumbo rolls shipments across the globe, and gaining advantage over local producers in certain regions.

“Even with limiting factor of protective local tariffs, the Belt and Road initiative might increase pulp shipments from Indonesia, toilet paper sales in Central Asia and Africa and export of Chinese made tissue forming and converting machinery.

“However, there are numerous issues that might limit or even fully eliminate untended effect of hastily growing infrastructure. Heavily populated South Asian countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh have very limited growth potential for tissue products due to cultural habits and low personal income.

Central Asian countries of the former Soviet Union might benefit from Belt and Road project by trading local natural resources for Chinese made consumer goods, however, tissue product consumption will still be in low single digits per capita in the near future.

In addition to local friction among these countries like recent squabble between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan over “grey” channel imports through quite transparent Chino-Kyrgyz border, Chinese exporters will meet competition from very strong tissue industry in Turkey.

“There is an obvious success of the five year-old company Oasis Brands in the United States claiming to be the fastest growing tissue brand in the country. This small tissue converter employs nearly 300 in the USA and sources its jumbo rolls from APP (Asia Pulp and Paper) – China-based #5 tissue producer in the world. However, despite an aggressive promotion campaign, Oasis Brands with its retail toilet paper and kitchen towels under brand name Fiora along with its sister company Solaris Paper, specialising in the AfH segment can be found only in Asian ethnic enclaves in the US and hardly be noticed anywhere including major supermarket chains dominated by industry giants Georgia-Pacific, Kimberly-Clark and Procter & Gamble.

“During the recent decade Chinese economic activity across African continent has rapidly increased especially in the highly corrupted countries of the Southern part. This expansion however has met quite strong resistance from local general population due to a common practice of bringing ethnic

“Chinese labour force to newly developed businesses. An impact on tissue product consumption increase is limited to several large city conglomerates where personal income is higher.

“Even with the further improvement of existing shipping channels as a result of the Belt and Road initiative, it is hard to justify economic benefits of bringing constant jumbo roll flow in the areas with strong local tissue industry in the Middle East, Europe or North America. However, this flow does exist in much smaller version in the “grey” market segments.”

A major shift in finance policy and a bid to dominate global trade

Bilateral policy banks: China Development Bank, China Eximbank, both known for their risk appetite, and hence their realistic assessment of possible losses in some of the world’s more blighted regions.

State owned banks: Bank of China, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, China Construction Bank, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Silk Road Fund, China-Asean Investment Co-operation Fund.

China is leading the new $50bn international financial institution the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, to which 21 countries have signed up. AIIB will be both a rival to the existing Asian Development Bank, an offshoot of Washington financial institutions, and potentially a complement to it.

Many see OBOR as the clearest statement of intent that China now actively seeks to influence global trade flows, increase its economic sphere of influence into Central Asia and beyond, and enable it to secure alternative routes for its energy supplies.

With US President Trump’s much criticised withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement suggesting that the US is slowly checking itself out of the western Pacific, China is seen to be moving to fill the trade void.

The strategy is multi-directional: with all of China’s key industries heavily concentrated on its eastern seaboard, to end over-reliance on shipping trade routes; to shore up its currency markets and to curb and better target the flow of currency overseas; and to build on existing trade projects with a targeted network of infrastructure links across continents.

Beijing has moved dramatically to redirect monetary and fiscal policies. During the last 15 years of intense industrialisation, China’s firms ran construction projects across an expanse roughly equivalent to the built area of all Western Europe.

It was accompanied by frenzied M&A activity. In the last year alone companies spent $220 billion on assets overseas.

As high as that figure is it is nevertheless down 42% year-on-year as Beijing strives to prop up the yuan by restricting the flow of capital outside the country and clamp down on what state planners call ‘irrational’ and debt-fuelled acquisitions – property, hotels, entertainment, European football clubs, movie studios – and provide new outlets for its goods on a huge scale.

But companies have proved hard to restrain. Regulators have made it tougher for buyers to win approvals for deals abroad, tightening the screws further since June.

As an example of what an all-encompassing buzzword OBOR has become, Chinese state media has claimed it is in effect a panacea for a multitude of problems including the Middle East peace process, start-ups in Dubai, currency trading, global poverty reduction, Xinjiang’s medical industry, Australian hotels, nuclear power, Polish orchards and, not to restrict its reach, the entire world.

Now deals will be reviewed in minute detail. One group of lenders has been ordered to assess its exposure to offshore acquisitions by several big companies that have been on overseas buying sprees – HNA Group, Dalian Wanda Group and Fosun Group for example, trying to get ahead for the long term.

European officials warned that the initiative has increasingly been hijacked by Chinese companies using it as an excuse to evade capital controls, smuggling money out of the country by disguising it as international investments and partnerships.

Investment will henceforth be under three categories – banned, restricted and encouraged. Scrutinised OBOR falls firmly into the later, and RMB internationalisation will be boosted by well-managed development as regional trade and investment networks further expand and deepen.

The outward emphasis is a move away from the previous Chinese strategy of attracting inward foreign direct investment (FDI) to one through which domestic companies are encouraged to invest outwards (ODI). The nature of ODI is also changing dramatically.

OBOR expansion into such diverse trading nations has made clear to Beijing that Chinese groups would benefit from the technological edge and local knowledge of western counterparts. Partnering western corporations also gives credibility on the money markets.

But sound management will be the key. China needs to avoid its engagement with recipient countries becoming unbalanced, resulting in manufacturing exports crowding out domestic production and resulting in trade deficits that may lead to economic and / or political tension.

Curbed or not, China’s acquisition-hungry conglomerates are still reported to be soaring in countries linked to OBOR, as elsewhere. Old habits die hard, and many economists believe that recent curbs on capital outflows will be reversed in the years ahead.

How will the US respond to China’s growing influence?

The US and China have made tentative moves towards greater co-operation on trade, and OBOR.

The trade deal announced earlier this year boosted the export market for US beef, and potentially for financial services and biotech products.

It is essentially a political agreement, addressing a subset of US-China trade issues, and springs from the 100-day plan to improve trade ties to which Presidents Trump and Xi agreed at their April summit.

This development comes at a time of heightened uncertainty in Asia over the US administration’s commitment to the region in light of Trump’s decision, on his second day in office, to pull out of the then 12-nation Trans Pacific Partnership which had been finalized by President Obama, after seven years of negotiations, as a core part of America’s effort to update and expand rules for trade and investment in the Asia-Pacific.

Remaining countries are lobbying hard to maintain the deal which eased barriers and tariffs on $356bn of trade last year alone.

The US has since made a major concession: recognition of OBOR, a move likely to be seen as signalling acceptance of one of the initiative’s underlying strategic aims—to secure a greater leadership role for China in Asia.

In a sharp shift in US policy from the Obama era, Donald Trump has sent representatives to an OBOR forum, marking a possible new period of American support for Chinese political and economic power and greater participation among American firms in OBOR endeavours.

The US urged a transparent bidding process, and has said that American companies have “much to offer,” and much profit to gain, from the OBOR programme. Construction, engineering, and finance firms are attempting to provide OBOR project with sophisticated American goods and services.

Already, GE is providing equipment, while Honeywell has been selling natural gas processing equipment to countries in Central Asia.

While American firms can certainly benefit by providing necessary tools to building the new Silk Road, ultimately it is China that stands to gain from trade and business deals with OBOR countries.

As fuller US participation remains a major question, China will forge ahead as it demonstrated when the US Congress put up roadblocks to giving China its rightful role in the World Bank… by simply setting up its own Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

Many countries, including western countries, made haste to support the AIIB. So with or without OBOR – these underlying trends are inexorable. OBOR is both a result of these trends and may well accelerate them.